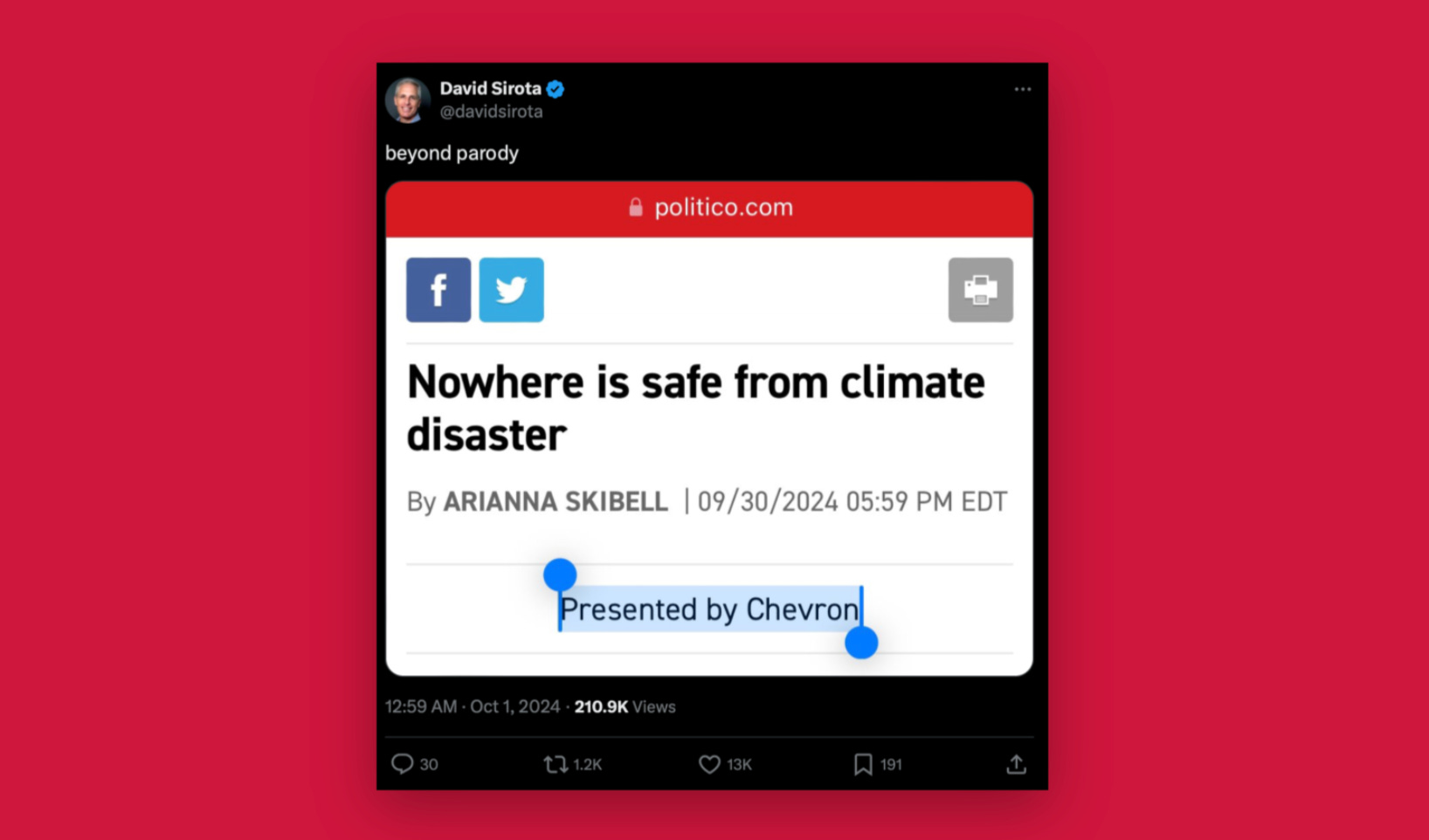

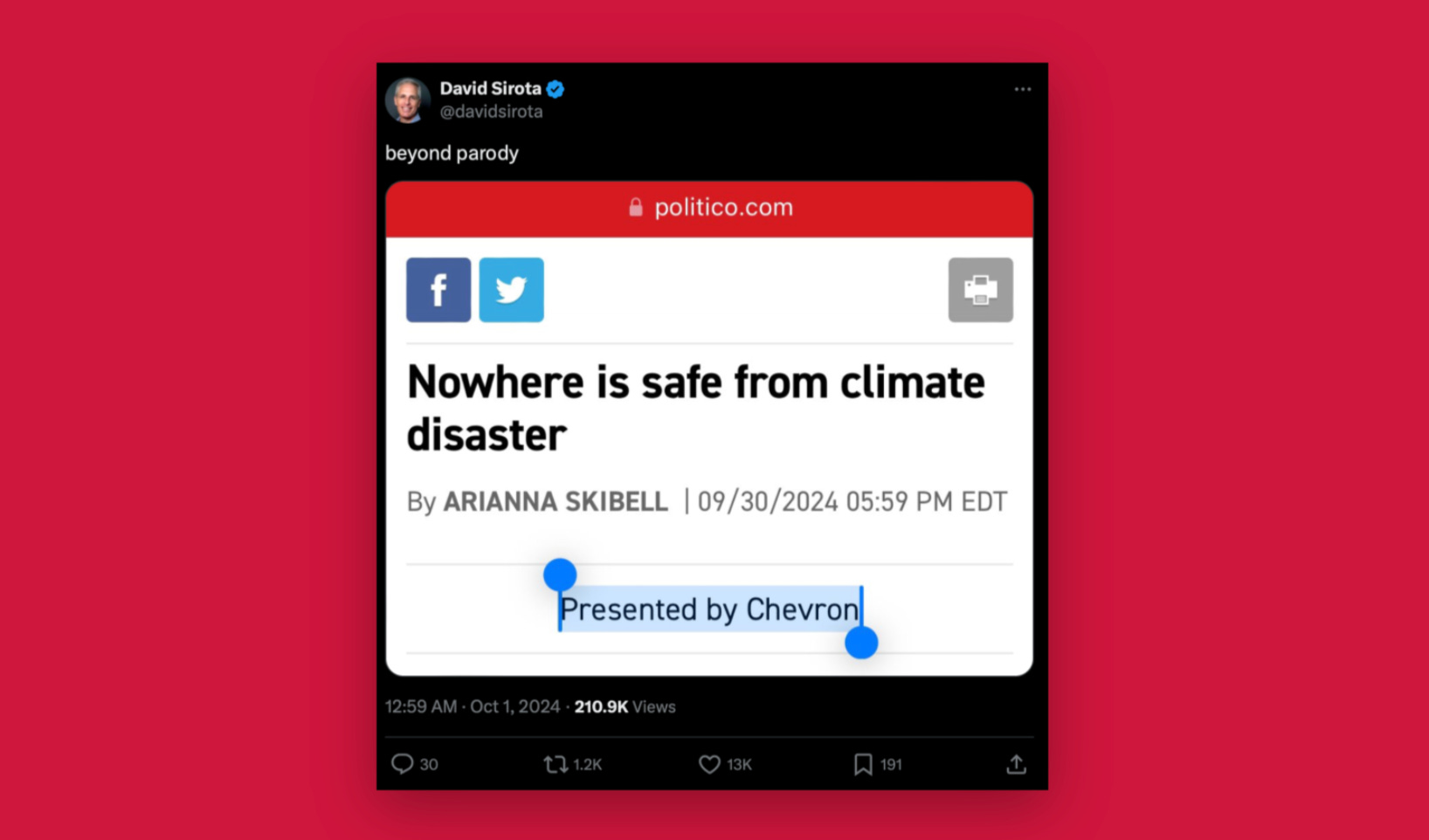

Chevron's risky new fossil fuel project

The oil giant wants to convince the public that its new ultra-high-pressure offshore drilling project, Anchor, is climate-friendly.

For a list of Hurricane Helene mutual aid resources, click here.

For a list of Hurricane Helene mutual aid resources, click here.