The political killings you don’t hear about

Across the globe, standing up for the planet can be a death sentence—and the perpetrators are almost never held accountable.

🌎 HEATED’s journalism is only possible thanks to paid subscribers. If you appreciate our fiercely independent coverage of climate and environmental issues, please support us. 👇

Many people in America consider Charlie Kirk’s murder a shocking, unprecedented act of political violence.

But the reality is, activists across the world are brutally gunned down and disappeared almost every day for their political speech. They just don’t have Kirk’s power or platform.

Take Juan López, an environmental activist from Honduras. He was shot dead in front of his family, friends and neighbors last fall as he was traveling home from church—six shots to the chest, one to the head. López had been fighting to protect the Carlos Mejía Escaleras National Park from iron oxide mining which has ravaged the area with pollution. Having faced years of prior threats and even jail time over his activism, López was supposed to be under special protection by authorities in Honduras. But those protections failed to materialize.

Or take Alberto Ortula Cuartero, a vocal environmental activist from the Philippines. The local government leader was publicly gunned down last fall by a passing motorbike rider. He was murdered after testifying against the Tribu Manobo Mining Corporation, alleging they were working on a falsified permit for nickel exploration. Cuartero was known in his community for mobilizing people against nickel mining, which is poisoning water and farmland in the region. His killer remains unidentified.

There’s also Julia Chuñil Catricura, who wasn’t publicly assassinated, but mysteriously disappeared while walking with her dog. The 72-year-old Indigenous Mapuche activist was well-known for speaking out about business interests destroying the native forest stewarded by her tribe. Chuñil had been threatened and harassed because of her advocacy for Indigenous sovereignty and stewardship over that land before her disappearance. Her dog returned from the walk. She did not.

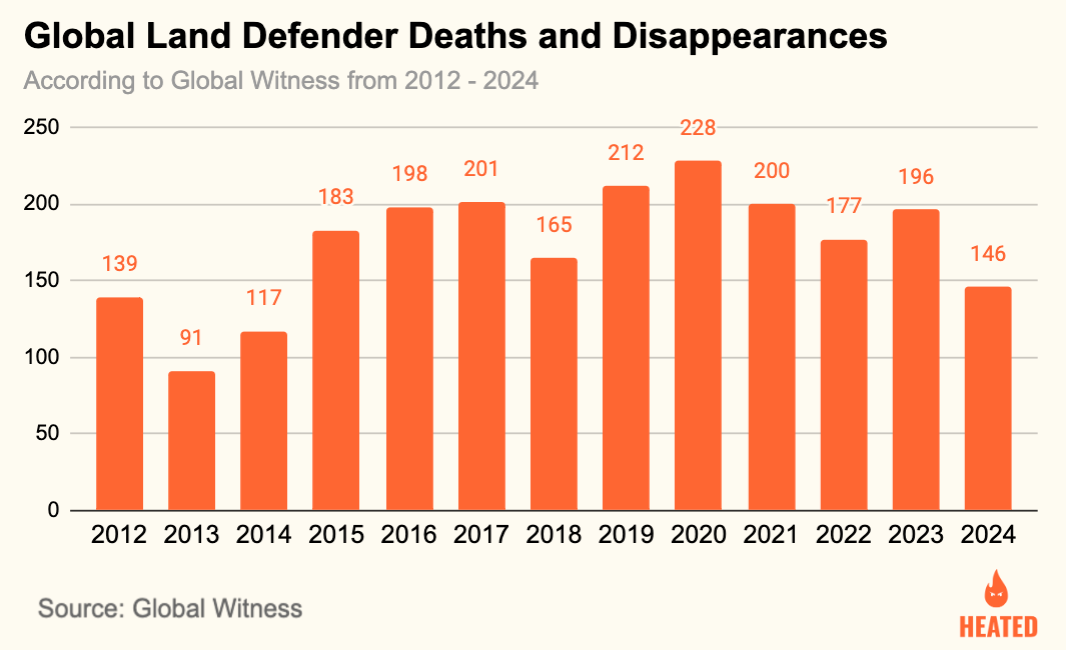

The activists mentioned above are just three of the 146 people who were murdered or went missing while defending their land, forests, and water from illegal mining, logging, poaching, and other environmentally damaging activities in 2024, according to a new report by the nonprofit organization Global Witness.

(You can read more about the other environmental and Indigenous activists murdered or disappeared in 2024 here)

While this figure is lower than the peak of 227 environmental and land defenders killed in 2020, it’s still a part of a frightening trend, said Laura Furones, the lead author of the report.

“Year after year, land and environmental defenders—those protecting our forests, rivers, and lands across the world—continue to be met with unspeakable violence,” she said in a statement. “They are being hunted, harassed, and killed—not for breaking laws, but for defending life itself.”

While many of the victims in Global Witness’s report were well known in their region or communities, their lack of access to an international platform—like Kirk had—has meant that their deaths have not garnered a fraction of the coverage or conversation.

López’s assassination was arguably the most internationally acknowledged murder of a land defender in 2024—his death was condemned by the United States and the United Nations— but he is still unknown to millions of people.

So why don’t we hear more about the deaths of environmental and land defenders when they happen?

Aalayna Green, a PhD candidate at Cornell studying race, conflict, and conservation, told HEATED that larger structural factors like racism, and histories of colonialism, have devalued the lives of non-white people, particularly Black and Indigenous people in other countries.

Every environmental defender murdered or disappeared in 2024 was from Latin America, Asia, or Africa, according to the report. Eighty percent of the killings occurred in Latin America. Nearly a third of the victims were Indigenous or of African ancestry.

“I think the thing that unites the permission of violence, or the justification of violence, is anti-Blackness,” said Green. “Whether that be intentional or unintentional, or conscious or subconscious, there’s a really big anti-Blackness problem that’s undergirding the dilemma of violence that we’re seeing today.”

Although Americans’ knowledge of world events and figures varies widely, language barriers and lack of news coverage beyond remote areas also play a role in downplaying the issue.

So what’s being done to address the problem?

One oft-discussed solution is state-sponsored protection plans for locals that might be under threat of violence or murder. But these often don’t work.

For example, Brazilian environmental activist Mãe Bernadete was under a state protection program when she was murdered in 2023. Bernadete was already under an incredible amount of protection, including security cameras in her house and military police who were making the rounds daily in her community.

That’s why many activists are calling on international bodies, like the United Nations, to step in and provide further protection. At COP30, which will be hosted in Brazil this November, activists will call on the U.N. to recognize and protect Indigenous land defenders as stewards of the land, as well as swiftly investigating killings and disappearances of land defenders.

“It’s clear that our knowledge, experience and practices as defenders must be at the heart of the solutions to the crisis,” Selma dos Santos Dealdina Mbaye, a colleague of Bernadete’s, said in the report. “But we cannot continue to protect the planet – including its biodiversity and its forests – if world leaders do not protect us from attack.”

Further reading:

The U.S., U.K. and EU are increasingly punishing environmental activists, too. From Monga Bay:

They might not have high rates of slain defenders like other parts of the world, but the U.S., U.K. and EU have spent the last several years introducing ways to crack down on people protesting in defense of the environment.

In the U.S., more than 20 states have passed laws that aim to protect “critical infrastructure” from protesters who obstruct roads, power plants and pipelines. Protesters face heavy fines for trespassing as well as felony charges that could land them in jail for years, the report said.

Without oversight, the clean energy transition could worsen violence against environmental defenders. From Grist:

According to the report, human rights defenders who spoke out against mining projects consistently experienced the greatest number of attacks over the past seven years. The authors say this is especially concerning considering the expansion of mineral production required by a transition to clean energy. All those batteries, solar panels, and wind turbines are going to require a lot of cobalt, nickel, zinc, lithium, and other minerals.

“We’re already seeing this level of attack, and we’re not seeing major producers of transition minerals have strong policies or practices in place about protecting defenders,” said Dobson. “There’s a real risk there and I think it’s an area that we’re very concerned about.”

It’s not just murder: Indigenous people defending their land face a disproportionate share of non-lethal violence. From Grist:

The Alliance for Land, Indigenous, and Environmental Defenders, or ALLIED, found that there were 916 nonlethal incidents in 46 countries in 2022 — or about five for every death. Nonlethal incidents range from written and verbal threats to kidnapping, detention, or physical assaults. The probable perpetrators identified by ALLIED include paramilitary forces, police, local government officials, private security guards, and corporations.

It’s difficult, but possible, to hold perpetrators of violence accountable. From Grist:

This year, Hudbay Minerals settled three lawsuits filed a decade ago by the Q’eqchi’, an Indigenous Mayan group in Guatemala. The Q’eqchi’ alleged that the Canadian-owned company was responsible for the sexual assaults of nearly a dozen women and the killing of a community leader during a land rights dispute. The Q’eqchi’ were compensated for an undisclosed amount.

Catch of the Day: Always alert Pompom trusts that justice will prevail.

Thanks to reader Cee for the submission.

Want to see your furry (or non-furry!) friend in HEATED? Just send a picture and some words to catchoftheday@heated.world.

The broader picture is that the global corporations can get away with these murders because local law enforcement can be easily bought and paid for to look the other way in these countries. Hiring a shooter is easy. They're a dime a dozen in the Latin American countries. It costs a little more to bribe the police and judiciary but for the corporations, it just another expense line on a balance sheet. The price of doing business in these countries, from Central and South America to Africa and beyond. The Afghans have a saying in their culture. No business is complete without some 'Baksheesh' changing hands. Western corporations have learned this since WWII and know how to apply it wherever they want to steal stuff from the indigenous peoples.

Thank you for shedding light on the reality of our world. Everyday, people throughout the world fight the power of profits over people. The history of this persecution and the destruction of people, their communities and their cultures must not be forgotten. Thank you to the families which have endured the losses and persevered.