The environmental terrorism of police choppers

The unequal surveillance by L.A.'s most notorious aerial polluters provide yet another example of why climate change and racial justice are inseparable.

This is part two of HEATED’s two-part series on L.A. police helicopters and climate change. To read part one, click here.

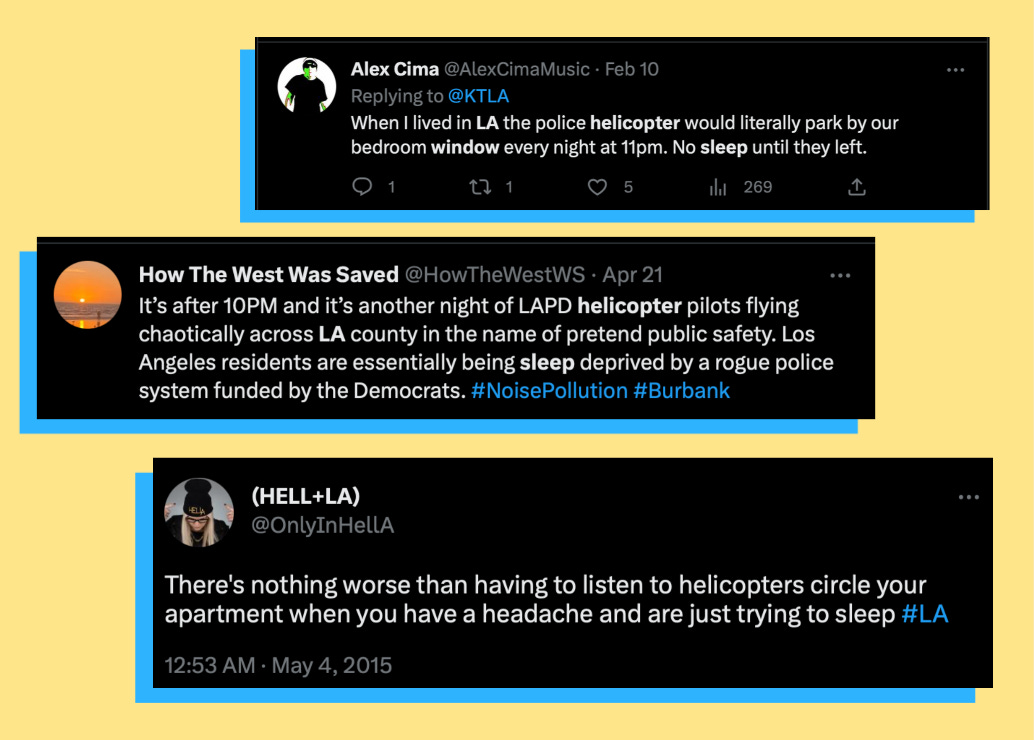

Suzanne Kite remembers exactly when she decided to surveil the surveilers. She was living in East Los Angeles, and the noise of police helicopters overhead woke her constantly in the night. Kite, an Oglála Lakȟóta artist and visiting scholar at Bard College, found the helicopters did more than interrupt her sleep—they affected her spiritually.

“One of the most important things for Indigenous people is to be able to dream, to be able to pray,” said Kite. “Even for non-Indigenous people, how can anyone do those things when they are the victims of sonic warfare multiple times a night?”

Kite decided to turn her camera on the police flying overhead. During the 2020 protests over the police murder of George Floyd, she and members of the L.A. Bird Watchers group gathered data on the police helicopters patrolling the protests. Another member of the L.A. Bird Watchers—Nicholas Shapiro, director of UCLA’s Carceral Ecologies Lab—expanded the study with flight pattern data from 2019 to 2020.

Preliminary results from their data, provided to HEATED, reveal that L.A. police fly more often over Black and Indigenous neighborhoods, and watched Black residents twice as many hours as white residents. Specifically, it showed that primarily white census tracts—areas with 4,000 white people–experienced 13.5 hours of helicopter surveillance that year, while primarily Black census tracts–areas with 4,000 Black people—experienced 28 hours.

The data also showed that L.A. police flew at lower altitudes over Black census tracts. If an area was more than 40 percent Black, Shapiro said, police helicopters often flew under the 1,000-foot threshold recommended by the Federal Aviation Administration. In one hyper-surveilled neighborhood, Watts, police flew a median height of 550 feet—almost exactly the height of the Washington Monument.

“That's true specifically of nighttime flights. So they're flying lower at night when people are sleeping,” said Shapiro, who is now studying the effects of disturbed sleep patterns on people’s brains and physical health.

The data not only shows yet another example of racist and often deadly policing in Los Angeles, Kite said; it reveals a pointed example of how racist policing furthers climate and environmental injustice in America. “They might seem separate, but they are all tied together because of the way that oppression and root harm works,” she said.

In today’s newsletter, L.A. residents and climate justice advocates tell HEATED why they believe the issues of climate change and helicopter surveillance are inseparable—and why defunding the police must be a critical part of the climate movement.

A message from Emily: This series is the product of weeks of original reporting by Arielle—and it’s free for everyone to read. That’s only possible because of the small number of readers who support us.

We don’t take advertisements, sponsorships, or grant money; we rely solely on our community to do this work. So if you value this reporting—and our commitment to 100 percent independent climate journalism that’s accessible to everybody—we hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber today.

How police helicopters are a form of environmental racism

As we explained in part one of this series, police helicopters are themselves harmful to the environment and the climate. In one year, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) and L.A. County Sheriff’s Department released 11,100 metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. That’s nearly three times more CO2 than last year’s highest-emitting private jet traveler.

But in the context of climate justice, police helicopter emissions are not as important as their impact on people’s health and well-being. Because in addition to adding more pollution to an already extremely polluted city, experts told HEATED, the constant surveillance is making L.A. communities of color more vulnerable to extreme heat and climate disasters.

The noise of the surveillance is one factor. Because the low-flying choppers are so loud, residents in Black, brown, and Indigenous neighborhoods often have to choose between a cool breeze and the sound of police, or the increasingly extreme summer heat, said Matyos Kidane, a community organizer with Stop LAPD Spying.

“I remember when I was a kid just making that negotiation on summer nights,” said Kidane. “Do you open the window because it's hot, and then hear the helicopters and wake up as a result of it?”

An open window can literally be live-saving in California, where deadly heat waves have already killed about 3,900 people in the last decade, with Black residents most at risk. That’s partly because communities of color have fewer trees or other forms of shade, but also because about 16 percent of households in L.A. do not have air conditioning, increasing their risk of heat-related illnesses like heat exhaustion, heat stroke, heart attacks, and long-term neurological effects. The need to close windows because of police surveillance thus adds another layer of climate vulnerability to the populations that are already most at risk.

In case you doubt how loud the choppers really are, a National Guard staff sergeant and U.S. Air Force reservist told HEATED that growing up with the sound of police helicopters prepared him to deploy overseas. Staff Sgt. Reymundo, who asked that his last name be withheld because he’s still active in the military, said he could sleep through the jets flying over his air base in Qatar.

“Some people who weren't used to that environment were like, ‘Oh man, this is so loud and so noisy,’” he said. “I'm like, ‘Oh, I can go to sleep just because of where I grew up.’”

The psychological impacts of helicopter surveillance–including the noise–are touted by supporters as an effective means of deterring crime. More recent studies, however, show that helicopters don’t reduce crime rates.

Instead, helicopters simply terrorize the communities they are meant to protect and degrade quality of life, said climate justice expert Dany Sigwalt, the managing director of Green Leadership Trust.

“There's a militarism that's coming into our communities that folks on the ground are going to be experiencing more and more, especially in the face of climate disasters,” she said. “If we're not pushing to defund now, it's going to be too late.”

The dangerous combination of racist policing and climate disasters

The Department of Defense calls climate change a "threat multiplier,” meaning its effects increase the risk of terrorism, instability, and civil unrest. These words echo the same language the LAPD uses to describe its need for aerial support: Helicopters are a “force multiplier” used for multiple law enforcement activities, including “civil unrest.”

Law enforcement agencies are also, as L.A. Sheriff’s Department Chief Jack Ewell pointed out in an email to HEATED advocating for the department, increasingly relied on for disaster relief. That means the same people that the police treat like enemy combatants will be at their mercy in a climate crisis.

This is partly why policing itself is a climate issue, especially for people of color, said Sigwalt.

She sees events like the police murder of environmental activist Tortuguita, who was shot 57 times; New Orleans residents shot by police as they fled Hurricane Katrina; and the non-evacuation of incarcerated people in Houston during Hurricane Harvey, as a precursor of things to come.

“To win on climate, we need to reinvent the power structures that haven’t functionally changed since slavery,” said Sigwalt, in an article she wrote after the police murder of George Floyd.

Unless anti-Black police violence is addressed by the climate movement, she told us, “There's nowhere really where we can feel safe.”

The ongoing battle to defund police choppers

This year, the LAPD will likely receive a 6.3 percent increase in their $1.9 billion operating budget, including $15.6 million for two new helicopters. That money could instead go towards social safety nets, say activists and community members. “They're solidifying this chokehold that police have on the city's resources that could be used to really address the things that cause violence in our communities,” said Kidane.

But that doesn’t mean there’s no path for people who want to ground L.A.’s police choppers. The L.A. city controller’s office is auditing the taxpayer-funded fleet, and will release a report later in the summer. And lawmakers looking for evidence to back up the complaints from residents will have it from Shapiro’s report.

Given that his lab’s preliminary data indicates that surveillance is actively harmful to communities, “a significant reduction in the use of airborne surveillance in Los Angeles would be supported by the evidence,” Shapiro said.

But Suzanne Kite, who first filmed the helicopters, said the data–while validating for her and other Indigenous, Black, and brown people’s lived experience–shouldn’t be necessary to inspire change.

“We shouldn't have to do all that work to back up community knowledge,” she said. “Our lawmakers and policymakers should believe their constituents when they say that they are being harmed or overpoliced.”

Read more:

Climate Activists: Here’s Why Your Work Depends On Ending Police Violence. Medium, June 2020.

Why communities fighting for fair policing also demand environmental justice. Los Angeles Times, June 2020.

These US cities defunded police: 'We're transferring money to the community'. The Guardian, March 2021.

Catch of the day: Reader Paula shared her sweet pandemic pup, Tindy, named after minister and civil rights activist Cordy Tindell Vivian.

Tindy loves to bask in the northern New Mexico sunshine and play tug o’war with her little buddy Greenie.

Want to see your furry (or non-furry!) friend in HEATED? It might take a little while, but we WILL get to yours eventually! Just send a picture and some words to catchoftheday@heated.world.

The helicopters are like building prisons and keeping the death penalty - their use plays well with voters by making politicians who support such things appear to be tough on crime. Many voters respond to such theatrics much more than they respond to the fact that these things don't actually reduce crime rates.

I'm not sure what the solution might be, other than protests to call attention to the problem. Articles like this certainly point us in the right direction.

I live in an area of LA where we get these flyovers constantly. When they get close to your house it’s really scary. I’m from Texas and was not used to this when I moved here, and thought it meant there was like an active criminal running around who could come in my house and hurt me--I’d close my doors and stuff. I learned quickly that these were just an intimidation ploy by the local police. I used to work across the street from an airport, and it’s kind of like that some days with the number of these invasive species birds flying over.