Our demand for cheap plastics is choking this town

Arielle goes on a "toxic tour" of Port Arthur, Texas to experience the local impact of plastics: the fossil fuel industry's strategy to survive the clean energy transition.

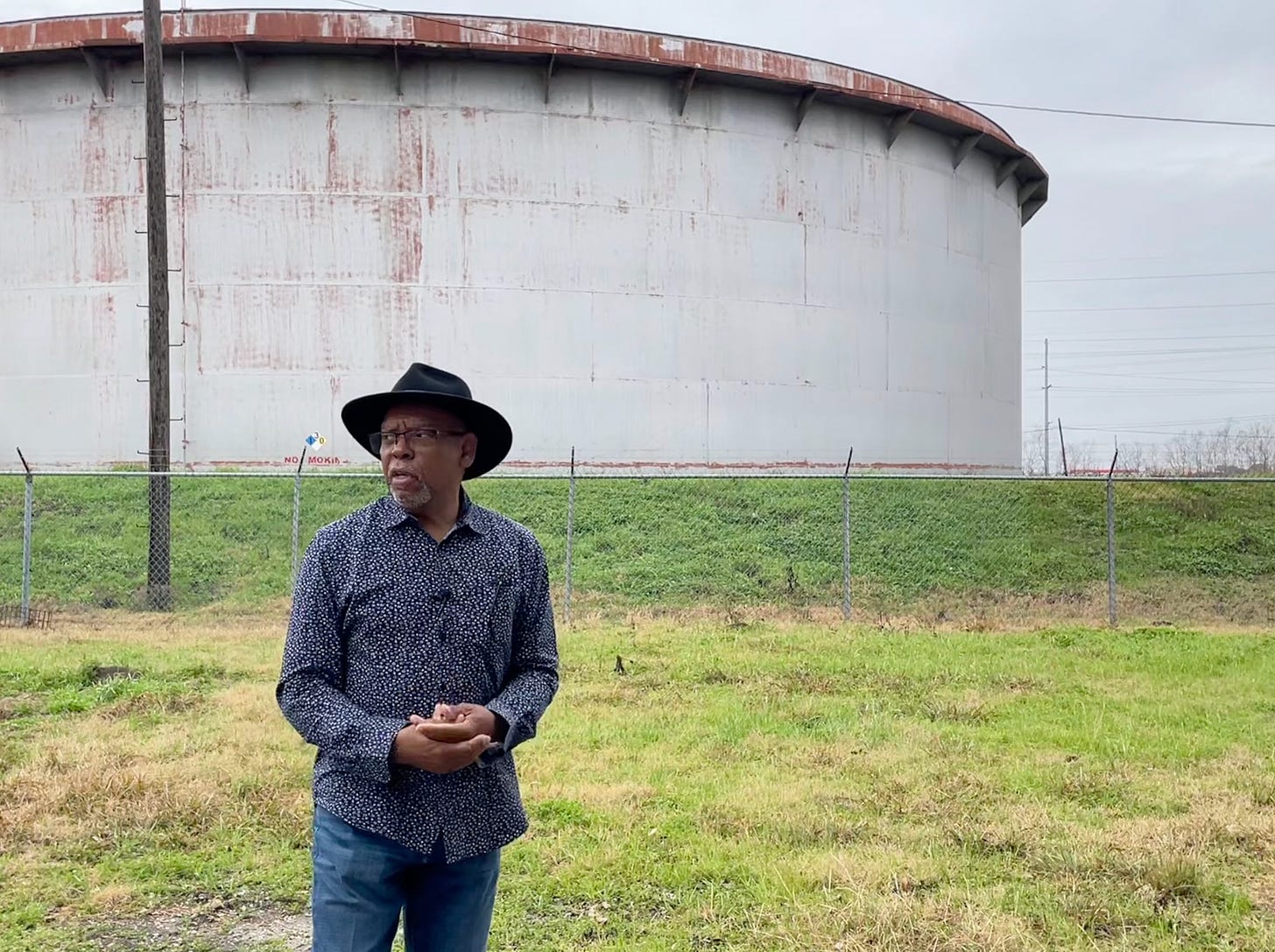

PORT ARTHUR, TX—John Beard Jr. stands in front of the largest refinery in North America, a beast of chrome shrouded in gray smoke.

The day is overcast, and the smoke billowing from the Motiva refinery behind him mixes with the fumes from the Valero petrochemical plant across the street. Refineries stretch across the horizon as far as the eye can see—an unbroken line of pollution.

After 38 years of working for Port Arthur’s booming fossil fuel industry, Beard knows exactly what is pouring out of those smokestacks. He tells the gaggle of reporters gathered around him to take a deep breath.

“I won't promise you it won't harm you,” Beard says, describing the rotten egg smell of hydrogen sulfide, a carcinogenic chemical. “But you'll survive. I mean, we've done it for 120 years.”

Port Arthur, where Beard was born and raised, is ground zero for some of the worst pollution in the country.

But it’s also where the fossil fuel industry is making its final stand against the energy transition, by betting on one of the most desirable and dirty products on Earth: plastic. The World Economic Forum predicts that plastic production will double in the next 20 years.

This is why Beard has invited some 40 journalists to his hometown: to experience the impact of the fossil fuel industry’s strategy on frontline communities.

Once an Exxon employee, Beard is now the founder of the Port Arthur Community Action Network (PA-CAN), a network he started to fight back against petrochemicals in his city.

Beard takes us on a “toxic tour" of Port Arthur, population 56,000, where the welcome sign tells us we’re in “energy city.” The town is quiet on a Friday morning—we see hardly any people as we pass neighborhoods still bearing the scars from Hurricane Harvey.

What we do see a lot of are refineries and plants, which are built so close to each other that we pull over every few minutes. Altogether, Port Arthur has 13 facilities, which sit next to schools, homes, and restaurants.

Our first stop of the tour is Texas Petroleum Chemical (TPC) Group’s petrochemical plant, which makes plastics. It shares a yard with a little league baseball field, and is next to a playground.

“People have gotten used to it and accustomed to thinking there's no harm or danger,” he says. “But there's always imminent danger when you're dealing with fossil fuels and petrochemicals.”

Beard knows intimately the dangers of working with petrochemicals, from his decades working in the ExxonMobil plant. Once during a safety training session, he says, a coworker vomited after inhaling too much benzene. That man was lucky, Beard tells me in an interview, because benzene can kill you. “Under high levels of exposure,” he says, “you may just pass out” and eventually die.

Related reading: A chemical disaster occurred almost every day in 2023

He shows me photos of the sky outside his house, dark with clouds of smoke. That smoke carries toxic chemicals into the air like benzene, chloroform, formaldehyde, sulfur dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and butadiene. And every time a facility flares, or burns off excess gas, it is allowed to “accidentally” exceed the federal limit.

Beard says he often wakes to the smell of rotten eggs, or tar-like creosote, or a slightly metallic odor. The Valero plant alone, which Beard can see from his kitchen window, has been accused of 600 air quality violations.

The toxic chemicals from the petrochemical plants spike cancer rates and other illnesses. People living in Jefferson County, which includes Port Arthur, have a cancer rate 18 percent higher than the average Texan, according to the Texas Cancer Registry’s most recent data. A study by the University of Texas Medical Branch found that people who lived near Port Arthur refineries were more likely to have heart and respiratory conditions, nervous system disorders, skin disorders, and headaches. Another study, published in the Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, found that nonwhite refinery workers in Port Arthur were more likely to die from cancer.

If the fossil fuel companies can’t operate “in a way that doesn't threaten the lives and health of people, then they shouldn't do it at all,” says Beard, as we sit in an empty Holiday Inn dining room that once held emergency meetings for Hurricane Harvey. “We shouldn't have to suffer and breathe polluted air because they want to make money.”

Port Arthur’s modest 144 square miles is worth hundreds of billions of dollars to the fossil fuel industry. And its fastest growing sector is not oil and gas, but plastic.

Most plastics today are made from ethane, a byproduct of fracking. Ethane “crackers” use steam to crack ethane molecules into the ingredients for plastic, including ethylene, propylene, and butadiene. Those plastics make everything from food packaging to footballs.

In Port Arthur, making plastic is even cheaper than elsewhere, because the refineries that supply fossil fuels to the ethane crackers sit conveniently next to them. The global plastics market was worth $712 billion in 2023, and is still growing rapidly. Plastic consumption is expected to nearly triple by 2060, according to the OECD.

That makes plastics, and the petrochemicals that make them, a second chance for a fossil fuel industry that is slowly being phased out. “Petrochemicals are the side hustle of the oil and gas industry, but they’re trying to make it their main hustle,” said Heather McTeer Toney, an activist with Beyond Petrochemicals, which organized the conference.

But in order to make sure their petrochemical side hustle is successful, the fossil fuel industry needs a social license to operate. To achieve that social license, the industry has been busily selling the public on the necessity of plastics to our way of life. Fossil fuel-funded groups have created educational materials for schoolchildren and national commercials highlighting how hospitals can’t function without plastic. Last year, major oil and gas companies sent representatives to the U.N.’s conference on ending plastic pollution to push the message that recycling can solve the problem (it can’t).

In the communities where they build their plants, global conglomerates like Valero, Exxon, and Chevron buy community goodwill by promising jobs. Beard says that when they first come into town, the oil and gas companies promise jobs to residents. But those jobs rarely materialize. Port Arthur’s unemployment rate has remained one of the highest in the country for years, while polluting industries have proliferated.

This pollution is concentrated in a handful of neighborhoods that are predominantly low income or communities of color. Eighteen communities, including Port Arthur, bear more than 90 percent of all plastic climate pollution reported to the EPA. More than 50 percent of Port Arthur residents are Black or Latino; almost one-third of residents live below the federal poverty line.

“They build the [refineries] in communities of color or poor people because they have little ability to fight back,” Beard said. “They don't have money for lawyers, and most of them don't even understand and know what it is they’re breathing in.”

Beard tells me that while working at Exxon, it was common for plant workers to die from disease before they got a chance to retire. His family, who have worked in the refineries for three generations, have also gotten sick. “I got family members that have migraine headaches, nosebleeds,” he said. “One of my children had to have a benign tumor removed.”

Thinking about his children and his grandchildren's future is what spurred Beard to take on the industry that is the only major employer in town. And part of his strategy is inviting reporters, politicians, and EPA officials to Port Arthur and reminding them that plastic pollution doesn’t stop in frontline communities. The wind doesn’t respect a fence line, he tells the tour group.

But the truth that Beard already knows is, unlike the people who actually live in Port Arthur, the journalists recording his words will go home to cleaner air at the end of the conference. As he takes us through another neighborhood with oil tanks in its backyard, he anticipates the question outsiders usually ask him: if the pollution is so bad here, why do people stay?

“This is where you're born, and it's where you raise your family in the house that your grandparents had,” he says. “Why would you move and have to start over?”

Activists fighting against plastics

In order to reduce petrochemical pollution, activists say changes in plastic regulation are needed. Eliminating single-use plastics, plastic packaging, and chemical recycling are a start.

Beyond Plastics president Judith Enck also called out the petrochemical companies pushing a personal responsibility angle, when most of the blame lies with corporations. Blaming people for how much plastic they consume "doesn’t recognize that we don’t have much of a choice," said Enck.

Still, activists do say that consumers can and should play a role in turning the tide. The U.S. is the largest exporter of plastic waste, with 40 percent of our plastic used for packaging. “The truth is we have to stop producing plastics,” said Enck, but “we don’t need a space-age breakthrough” to do so. The alternatives are already available: paper, metal, glass. We just need consumers—at least, those with the time and financial privilege to do so—to help fight for those alternatives.

Beyond Petrochemicals: This activist group helps frontline communities fight petrochemical projects and pass anti-plastics legislation. Recently, they introduced a bill to the New York State legislature that would change the definition of recycling to exclude toxic “chemical” recycling favored by the plastics industry.

Port Arthur Community Action Network: John Beard Jr.’s group is currently fighting two new liquified natural gas plants, which Beard said should have stronger pollution controls.

Rise St. James: Sharon Lavigne founded this environmental justice group to fight polluters in Cancer Alley in Louisiana. Lavigne and other activists filed complaints with the EPA alleging that the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality had engaged in racial discrimination for not enforcing their rights to clean air and water. The EPA dropped its investigation after Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry sued. The group is also battling a new Formosa Plastics manufacturing complex in the state courts.

T.E.J.A.S: One of Texas’s leading environmental justice organizations, Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services is operated by the Parras family: longtime justice advocate Juan Parras, his son Bryan Parras, and daughter-in-law Ana Parras. Among other campaigns, the group advocates for stronger EPA regulations surrounding high-risk chemical facilities, in order to prevent explosions and other disasters.

Know of other activist efforts to fight plastic and petrochemical pollution that we missed? Let each other know in the comments!

Correction: A previous version of this article misidentified the TPC petrochemical facility as an Indorama petrochemical facility, and Beyond Plastics.

Catch of the Day: Hi all—Emily here. If you read last week’s newsletter, you know that my family has been preparing to rehome our golden retriever, Mason, due to my mom’s recent hip replacement surgery.

I’m both very happy and still a little sad to report that Mason is now safely and happily with his new family, and they have been graciously sending us pictures and videos of Mason’s new fun-filled life!

Here’s him playing with one of the neighbor’s dogs in the closed-down community garden.

As for my mom, she’s doing well! She came home from the hospital on Saturday, and it’s been all physical therapy assisting/medication scheduling/shower bar installing ever since. We even went on a (very slow, equipment-assisted) walk outside today.

Thank you all so much for your kind words and support. They’re really helping us get through it!

Want to see your furry (or non-furry!) friend in HEATED? It might take a little while, but we WILL get to yours eventually! Just send a picture and some words to catchoftheday@heated.world..

I worked in Ghana for 3 years - 2015-18. A few colleagues traveled there to see the mountain gorillas and when they came back they said Rwanda had banned plastic bags. Rwanda!

Before Ghana, I had spent 3 years in Cairo, Egypt. In both countries, plastic bags are ubiquitous. There are roadside stands everywhere, selling anything from fresh fruit & vegetables to every imaginable sort of trinket or gadget. Plastic bags are used by EVERYONE in both countries, and I'm guessing most other nations on the planet. And why not? They're cheap, strong, versatile, etc.

But - Rwanda!! They banned those things nearly 10 years ago. Europe is not far behind - many countries in Europe charge a fee for plastic bags, instead of giving them away by the millions like our stores here in the US.

There are plenty of replacements for single-use plastic out there; what we lack is the political will to stand up to the fossils.

It's a shame that the corporations get away with killing people like this. A slow death. But then, I am retired military and I get the same treatment from the government. 'Oh we're sorry we exposed you to toxins or made you take toxic medicines. It's incurable so here is some money for you trouble. Have a nice life'. Much the same for people like those living in Port Arthur. The corporations are sorry but carry on anyway.