New internal Big Oil documents just dropped

The Senate Budget Committee is officially reviving the House Oversight Committee’s investigation into fossil fueled climate delay.

In 2021, Congressional Democrats subpoenaed Big Oil for internal documents detailing the industry’s role in worsening the climate crisis.

Some of the documents have already been released. But today, we got some more.

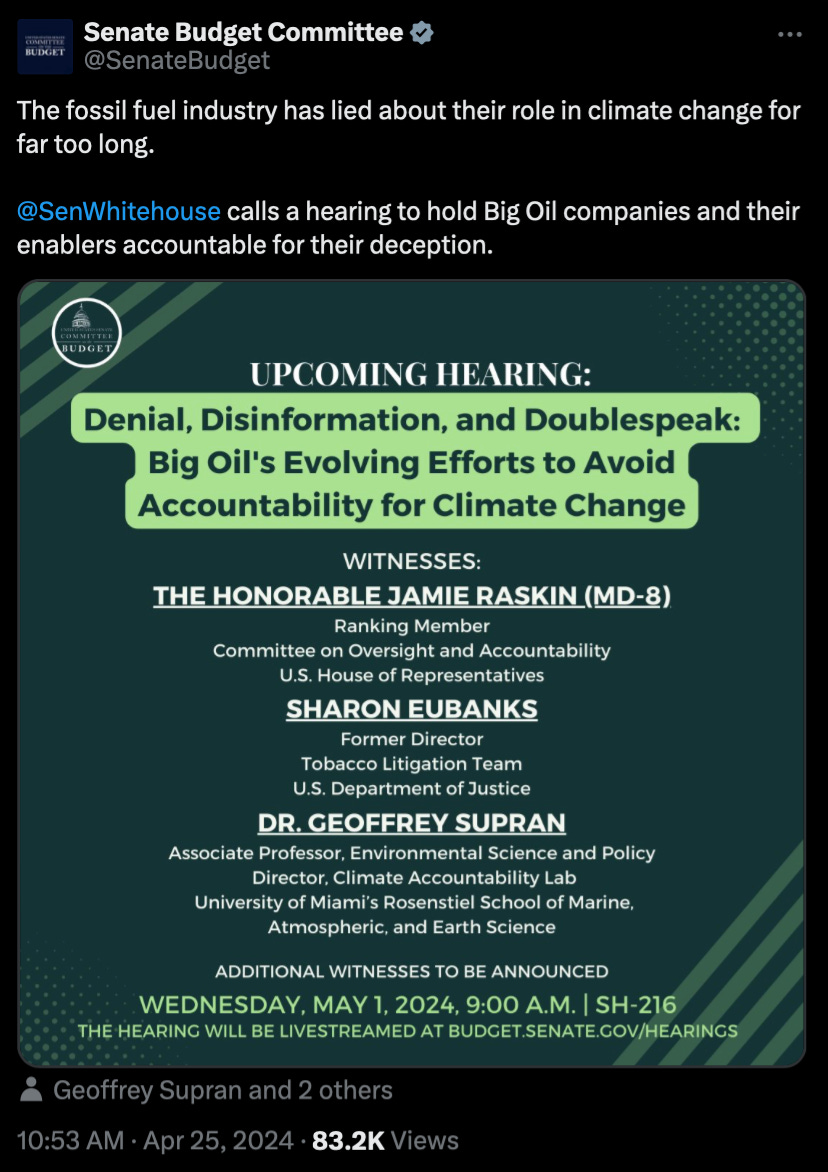

The internal materials are from Exxon, Chevron, Shell, BP, the American Petroleum Institute, and the Chamber of Commerce. They’re being released today as part of the Senate Budget Committee’s upcoming hearing on Wednesday morning, titled “Denial, Disinformation, and Doublespeak: Big Oil’s Evolving Efforts to Avoid Accountability for Climate Change.”

Both the hearing and the documents mark the revival of the House Oversight Committee’s two-year investigation into the fossil fuel industry, and its role in misleading Americans about climate change. That investigation was put on ice when Republicans won back control of the chamber in late 2022.

Democrats say their new findings provide “a rare glimpse into the extensive efforts undertaken by fossil fuel companies to deceive the public and investors about their knowledge of the effects of their products on climate change and to undermine efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions.”

HEATED got a chance to review the new documents prior to their publication today. And while we don’t think the revelations are necessarily all that “rare,” here are five things we found notable.

1. BP really, really loves Princeton

To influence academia, fossil fuel companies have spent at least $700 million on partnerships with U.S. universities. The longest-running of these partnerships is between BP and Princeton.

The new documents provide some insight into why: because Princeton gives BP unprecedented access to discussions about research. In 2016 emails, BP officials discussed cutting funding to Harvard and Tufts and boosting it for Princeton, because research discussions at Harvard and Tufts “are directed by the universities and much less relevant to BP.” They said “personality and structural issues” at Harvard and Tufts made it “difficult to achieve the same BP focus.”

Achieving a “BP focus” meant two things: pushing research about the benefits of carbon capture and methane gas. And that’s what Princeton’s Carbon Mitigation Initiative did.

In 2018, an internal BP presentation marked “confidential” recommended Princeton CMI director Stephen Pacala as a preferred expert in defending methane gas as a climate solution. And in a 2020 email, BP officials discussed an upcoming call with Pacala, in which BP would recommend developing a net zero plan “with emphasis on CCUS [carbon capture utilization and storage] — building ‘backbone’ of pipelines to transport carbon from emitters to the Permian and Gulf Coast sites.”

CMI did eventually develop a net zero study with an emphasis on carbon capture. BP officials celebrated, writing, “Princeton’s net zero study is expected to be a guide for the Biden Administration.”

Today, sure enough, the Biden Administration is making massive investments in carbon capture—just as BP’s vice president of U.S. policy and regulatory affairs predicted. In a 2020 email, he said BP’s relationship with Princeton was “becoming increasingly synergistic.” If Biden won, the VP said, “I would not be surprised to see some of our friends in senior government policymaking roles, as well!”

2. Oil companies know they can’t meet their public climate goals

While they publicly tout their efforts to fight climate change, oil companies privately say they don’t believe the world could ever reach a safe, livable climate.

For example: Exxon first publicly supported the Paris Agreement in 2015, but internally the company revealed that it did not believe the climate treaty’s goals were realistic. “We don’t yet see the world even approaching a 2°C pathway … let alone a 1.5°C pathway,” Exxon’s former manager of environmental policy and planning Peter Trelenberg wrote in a 2018 email. “Both 2°C and 1.5°C would require unprecedented changes to the global energy system and economy, at a rate and scale never before demonstrated, and with technologies not yet available and affordable.”