How fossil fuels mutated Milton

Climate scientists tell HEATED the historic storm represents "the profound irresponsibility and culpability" of polluters.

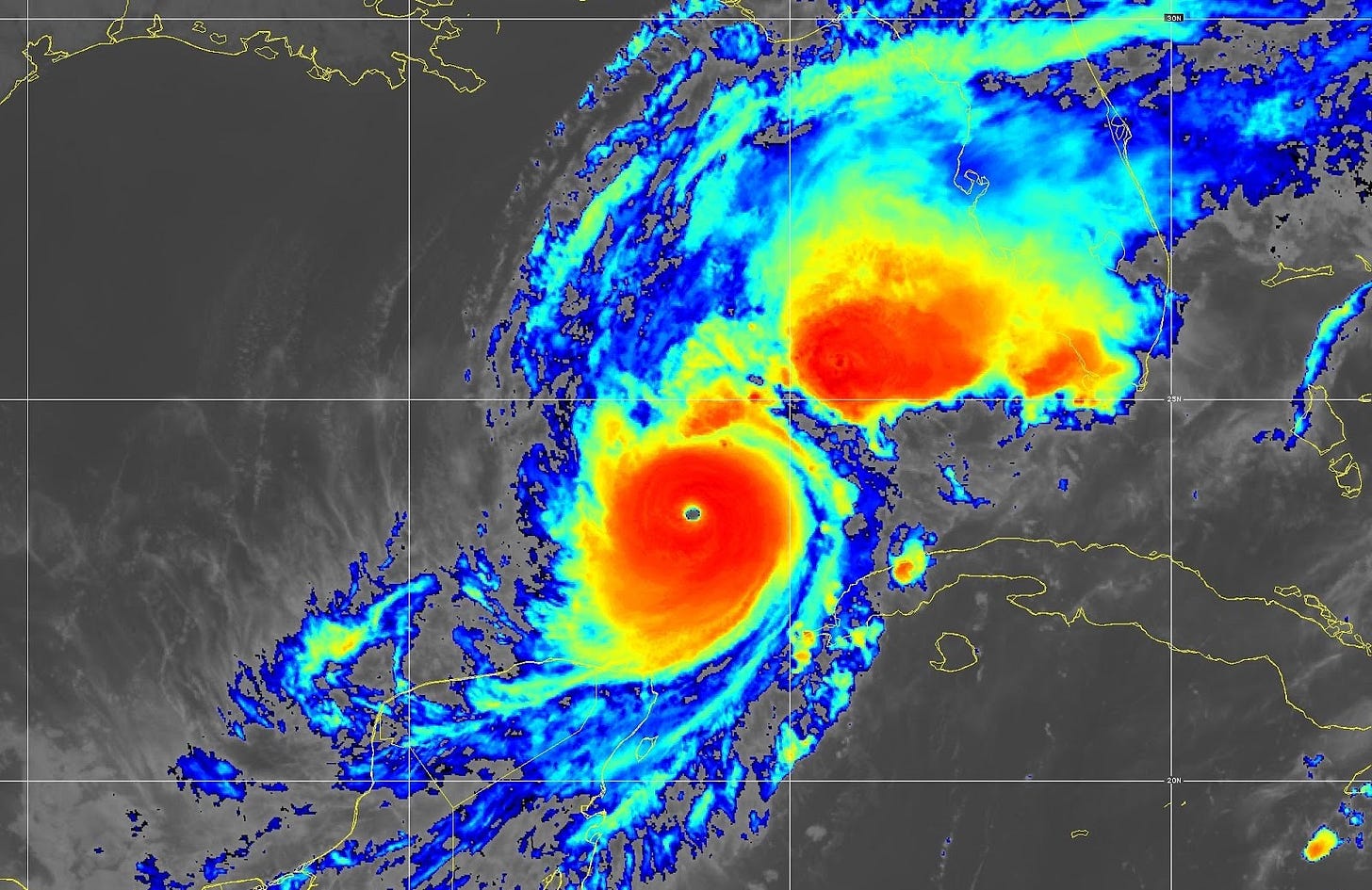

For scientists who study the effects of climate change, the scariest thing about Hurricane Milton is not simply its historic strength. It’s the fact that Milton grew so stro…