Advice from climate journalists

You all might not be climate journalists, but you should know what makes a good one. Here's what some of the best in the business say.

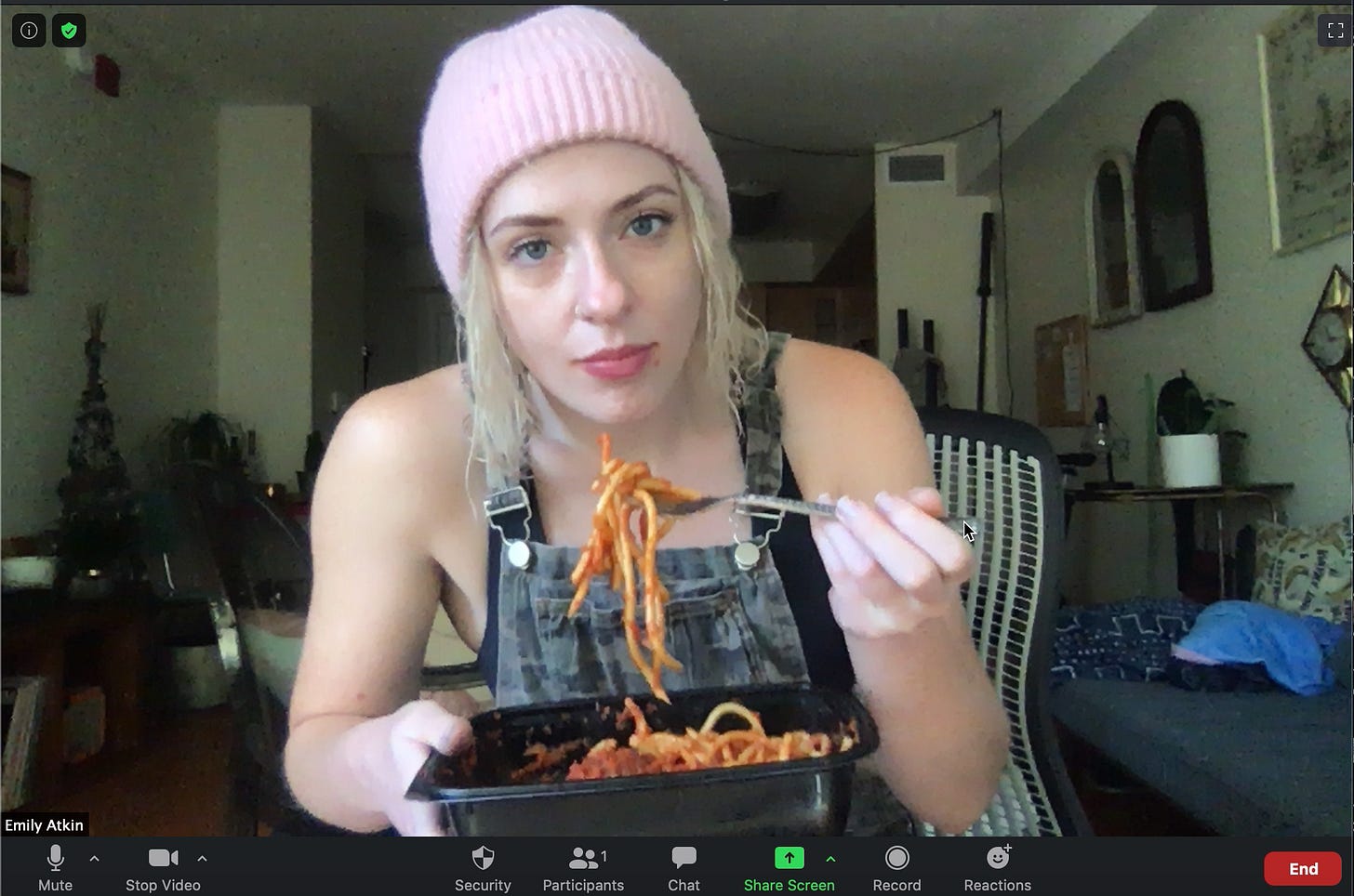

Me eating pasta waiting for a one-on-one Zoom meeting with one of my students. I am a Cool Professor.

I’m teaching climate journalism course this semester for my alma mater, SUNY New Paltz. It’s a three-ish hour zoom class that takes place every Tuesday afternoon.

My students are a group of fifteen bright young journalism majors, and their only major ass…